Ecology/Consumerism

‘If ecological action means not doing as much damage, rather than doing things more efficiently, then it is not ecological to insist or slap upside the head or the other similar current modes of supposedly ecological data delivery in general. These kinds of action are like trying to wake us up from this bardo-like dream - but the dreamlike quality it’s precisely what is most real about ecological reality, so in effect, throwing out factoids and statistics in information dump mode is making ecological experience, ecological politics, and ecological philosophy utterly impossible.’ (Morton, 2021, p.23)

My work investigates the recurring themes of ecology, consumerism, hauntology and meta-modernism. By using found objects, assemblage, ready-mades, recycling, upcycling, and repurposing, I explore and engage, politically and socially with my environment to better understand the world around me.

Ecological Thought is a term established by Timothy Morton in his books The Ecological Thought, Hyperobjects, All Art is Ecological, in which he states that ‘all forms of life are interconnected, and this connectivity penetrates all dimensions of life’. This principal is central to my art practice where I explore connectivity and ecology. I also support through my work another of Morton’s Theories that not only humans have agency, but objects too.

In his book Morton gave the following example ‘As you slip embarrassingly toward the ground, you notice the floor for the first time, the colour, the pattern, the material composition— even though it was supporting you the whole time you were on your grocery mission (Morton, 2021, p.9)

During the current ecological crisis, as we ‘slip embarrassingly towards the ground,’ it seems that objects become, or need to become, more and more substantial and visible. Especially when it comes to our awkward relationship with waste and the circular economy.

To explore this, I incorporate in my work found objects such as household packaging, recycled bottles, soda cans, mesh, metal, polyester, and paper. I’m interested in creating a new narrative for these objects where I highlight their usefulness, beauty, and utility by creating a new reality for them.

I was intrigued by Morton’s thinking, and I went on to read about Graham Harman opposing the idea that humans are in some way special and believed that all non-human objects are at once autonomous, they have their own meaning and connections. That this complex interplay between non-human objects can change the relationship between objects used in artworks and the observer. This is particularly relevant to me as the use of found objects has always been central to my work as well as the ecological narrative, and these two different but connected thoughts gave me a new and important understanding of why I’ve been drawn to these objects in my work. How if I could better understand this interplay mentioned by Harman it might positively affect the development of my art.

Fig. 1 Joseph Beuys, 7000 Oaks, 1982

Joseph Beuys, German artist, is a pioneer of the deep ecological thinking that developed in the contemporary art world in relation to the ecological crisis. By overcoming the thinking around the divergence of men from nature, he initiated the concept of social sculpture.

It is my desire to unravel the physical and causative components of the everyday objects vis-à-vis their role in ecological awareness. I’m inspired by Beuys’ central belief that the power of universal creativity will bring universal change.

I witness that ecological awareness is more and more prevalent in contemporary art. Artists like Sarah Sze (1969- ), Yu Li (1985- ), Tadashi Kawamata (1953- ), Helen Marten (1985- ), Michael Landy (1963- ), Ai Wei Wei (1957), and many others use in their installations many disparate approaches to deliver their message of environmental impact through using found objects and debris.

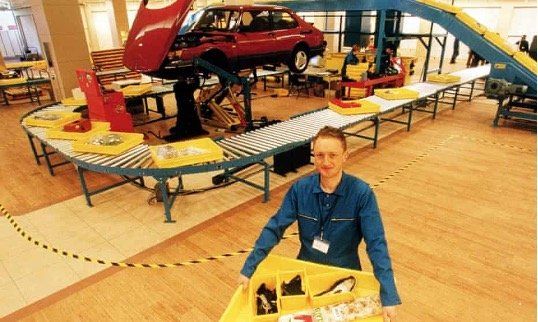

Fig. 2 Michael Landy, Break Down, 2001

In his work Break Down (2001), Michael Landy destroyed all his belonging in an attempt to protest consumerism. However, unexpectedly he became the perfect consumer in addition to creating ‘valuable’ works of art.

The unique way he approached this project by initially cataloguing everything he owned then destroying them is inspiring. He aimed to raise awareness of the consumerism crisis, the obsession of ownership and the negative impact consumerism in the Western society has on our environment. He intended to free himself from the emotional connection to his everyday possessions. This work objective was to signal a strong ecological message.

Michael Landy planned in detail the destruction of his items, conversely, I plan in detail how using found objects in making can raise self-expression and self-esteem. Additionally, it can boost mental wellbeing as it creates symbolic but often emotional links to past experiences and relationships.

Landy said: “I always try to look at things that have no value and give them some kind of visibility”. This is particularly important in what I aim to achieve in my practice.

In my practice, I use my personal discarded objects to explore how inanimate objects can carry a ghost of their past function and cultural meaning forward into the present and how this can influence our relationship with found objects and increase their ecological meaning. To challenge their perception and drive reappraisal I paint these objects in bright red paint.

Hauntology

‘The concept refers to a collective contemplation of alternative possibilities – those which have failed to occur or have been negated by our modern society’ (Amelia Carruthers)

Jacques Derrida (1930 – 2004), an Algerian born French philosopher and historian, is the creator of the term Hauntology, which was introduced in his book Spectres of Marx in 1993 and is a combination of the terms haunting and ontology.

The concept of Hauntology is a central thought in the ecological message I aim to represent in my work. That objects carry a ghost of their past forwards with them is possible reason why Harman believes that objects are autonomous and why Morton thinks they become more visible. A key theme of my art has been how we are conditioned by our past and this affects our present without us being aware of it. I think that this conditioning is also in how we react to objects around us based on our experience of them, they carry forward meaning that ‘haunts’ our present. For me for example the Coca Cola bottle had real cultural significance when growing up in Eastern Europe. I’m interested if we can use this relationship with inanimate objects properly, we might be able to better communicate an ecological thought through them.

In the 1980’s, in China a movement called Political Pop emerged that was a direct reaction to the steep economical evolution. It was a mix between Western pop art and Socialist Realism art movements.

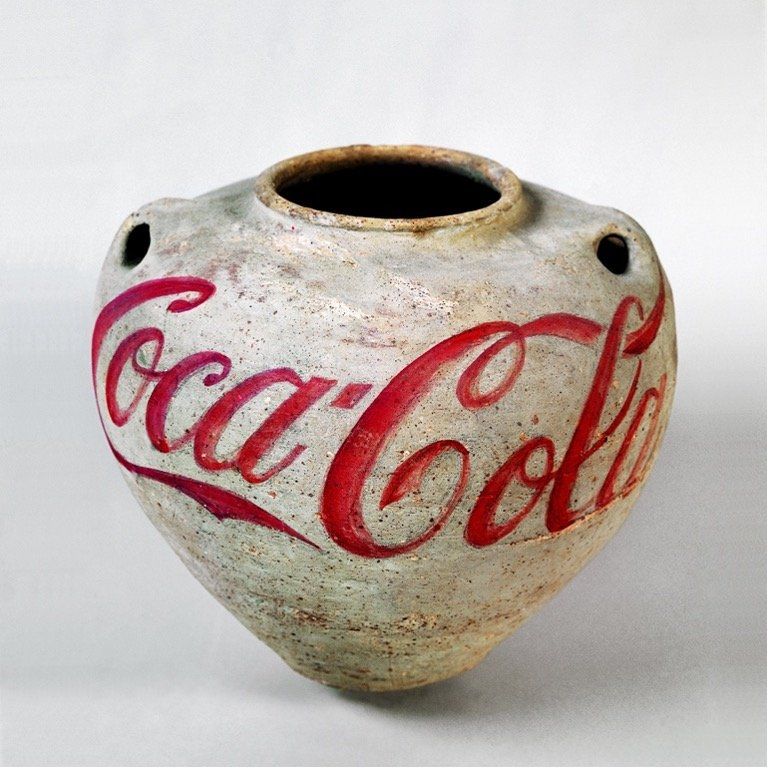

Fig. 3 Ai Weiwei, Han Dynasty Urn with Coca-Cola Logo, 1993

Ai Weiwei (1957- ) uses the Coca-Cola logo – a quintessential emblem of global consumerism - in his ongoing series Coca-Cola Vase, which he paints carefully onto Han Dynasty vases to provoke viewers to recognize how China’s engagement with the West has had both destructive and creative consequences.

The use of the Coca Cola logo is equally banal and semi-ironic. The Coca-Cola logo is a perfect example of Hauntology where the return and persistence of the iconic logo is used to represent a cultural past. It’s a favoured motif for artists through time. Artists like Salvador Dali (1904 – 1989) in Poetry in America, (1943), Robert Rauschenberg in A Coca-Cola Plan (1957), Andy Warhol in The Grocery Shop show (1962), and many others, used it in their art works for its multiple cultural references.

I grew up in a communist country where the Coca-Cola and Pepsi images were the strongest symbols of western culture symbols. Finding these crushed cans on the paving on my walks here in UK - casually discarded - made a big impact on me. They underlined the large differences between cultures and values.

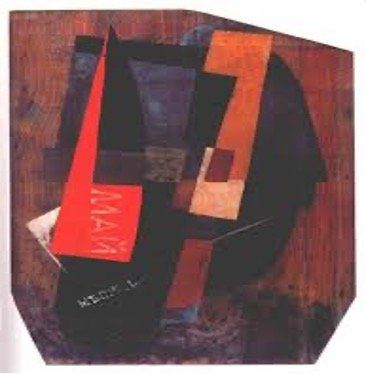

Fig. 4 Vladimir Tatlin, Monument to the Third International (1920)

Founder-member of Soviet Constructivism (this art current was one of the most influential in my life growing up in an East European country with Socialism Realism Art), Vladimir Tatlin is known is known particularly for his model for the Monument to the Third International (1920) (photo), which became a symbol of Constructivist art.

Other members of the same art movement I was familiar growing up are: El Lissitzky, Naum Gabo, Laszlo Moholy- Nagy, Kasimir Malevich. They made works that glorified working class heroes and communist achievements, something that I am familiar with. Tatlin’s work, Monument to the Third International (1920), that reflected his utopian vision of the future, was a cross between an architectural model, a piece of scientific apparatus and a Dada assemblage.

Talin was inspired, when he visited Picasso in Paris in 1913, by the Cubist mixed media constructions, the use of glass, plastic and other industrial oddments.

Socialism Realism ‘heroic idealization of the working man was its leitmotif, its pictures were characterized by an easily understood form of realism, painted in bold colours’. He developed a completely new approach to making artworks focusing on construction.

I am interested in using the same colours and the same principles as Tatlin, but with the opposite intention, to change behaviour raising awareness of climate issues and environmental problems.

Fig. 5 - 6 Vladimir Tatlin, Right Counter-Relief (1914-15) and left Komposition (Monat Mai) (1916)

Themes and words that interest me in relation to this are simplified lines, monochromatic colour scheme, architecture, constructions, social utopia, primary colours, direct and simplified message, universality.

The colour red, widely used in Soviet Constructivism and Social Realism, and in polar opposite for the Coca-Cola logo – a quintessential emblem of global consumerism, is unmistakeably intense in its emotional register.

The colour red, one of the first colour to be used in prehistoric art, is the main I use in my work in relation to the hauntological theme. I use the semiotics of the colour red to accentuate the hauntological effect of the objects I use. Because red carries so much meaning it creates a strong association with the objects previous lives and allows me to play with this in my work and challenge this perception and conditioning.

Humour/Playfulness

“It belongs to the borderline between art and life. In reality, it is life itself, but shaped according to a certain pattern of play.” (Bakhtin, M Rabelais and His World)

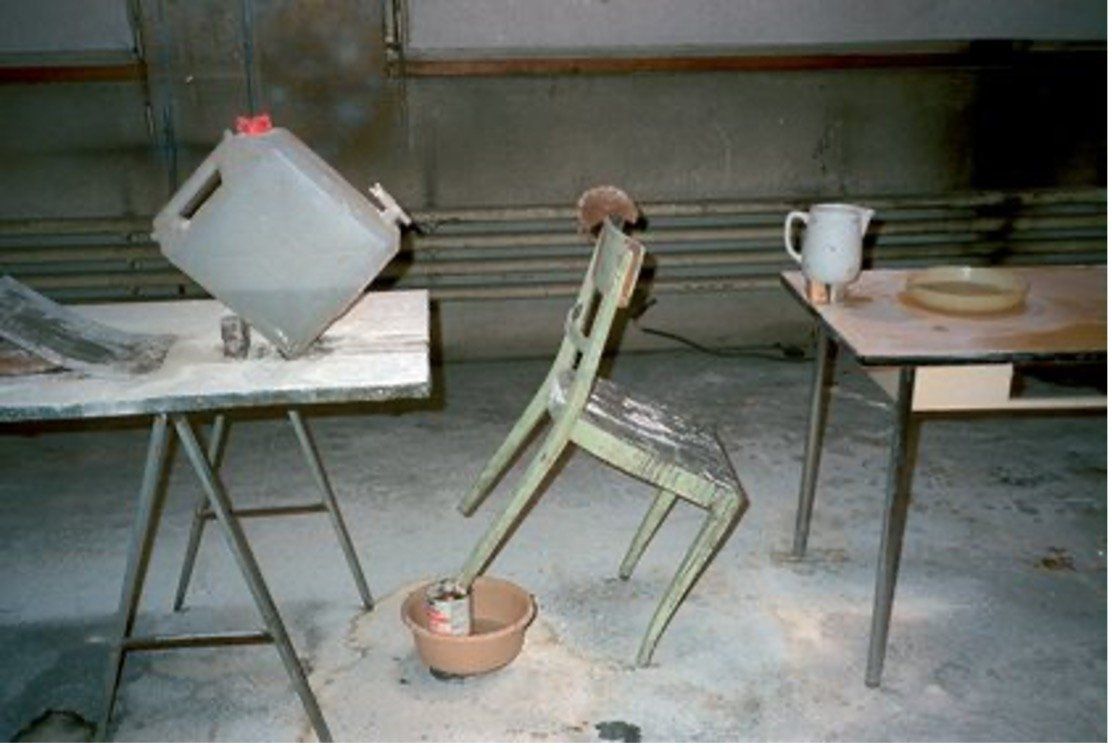

Fig. 7 Peter Fischli and David Weiss, The Way Things Go, 1987, Film still

Peter Fischli (1952- ) and David Weiss (1946 – 2012) in their series called Equilibres, also known as Quiet Afternoon from 1984, balanced everyday household objects in an absurd and comical context. These constructions are ‘bold, fragile balancing acts comprised of objects that just happened to be at hand constructed in situ and photographed.’ (Frey, 2016)

I find this series of work incredibly playful and joyful. With their works, Fischli, and Weiss have secured a type of play which every one of us is familiar with from childhood regardless of whether you were good at make believe, and they have conveyed it unchanged into adulthood delivered through handiwork. As Arthur Danto (1996) said ‘they carried it intact into adulthood to clarify that there would be something untainted in their play regardless of whether it may be contended that all of art is in some way or another consistent with types of play. For almost no art appears so prominently to display the imaginativeness of playful youth as does theirs. It changes knives, forks and spoons into mountain climbers and makes gymnastic performers out of vehicle tires so that they seem to have a will of their own’. (Danto, 1996, p.97)

For this series, they also made a thirty minute movie named The Way Things Go where they used the same everyday objects to create a chain reaction with a hypnotic kinetic energy. It inspired me to make my own film.

In The Way Things Go, Fischli and Weiss, created a butterfly effect shown through the apparently unplanned interaction of the objects, completely different to the series Equilibres that only show static images. The interrelated movement of the objects in the film has strong ecological undertones in addition to the playfulness of the work.

The lively tone of their work inspires me into looking at the world around me. The more I look the deeper the message is, highlighting that childhood play is the most crucial act of our early life. It seems that humanity is directly influenced by our education during this time and play is a major part in this process. It creates our views and habits; this is the conditioning of our early years. Fischli and Weiss are aware of the importance of childhood play when they created their constructions. This connection to the past is a way of strengthening the relationship with the objects that inspire this connection.

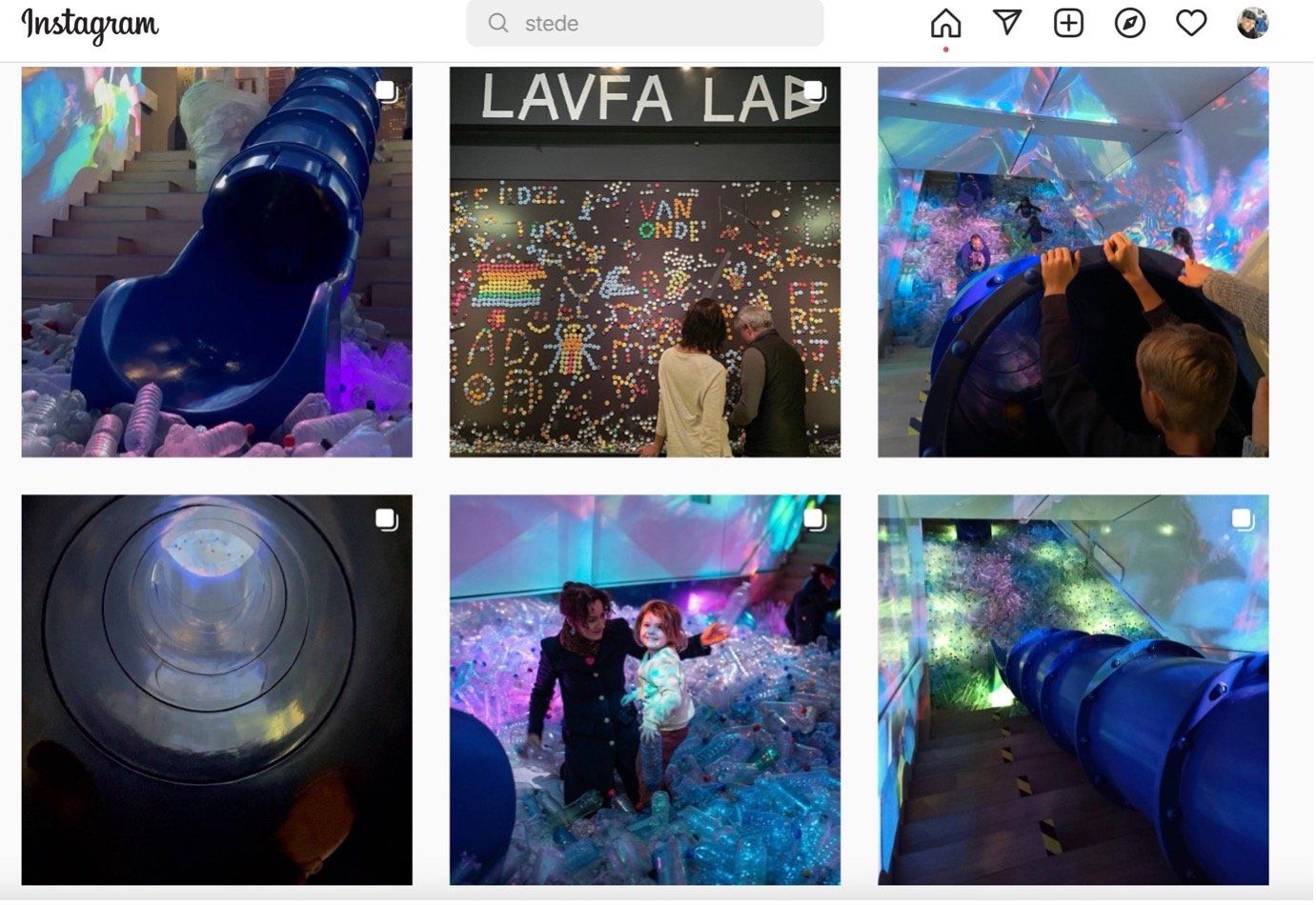

Fig. 8 @hotmamahotcollectief for Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, LAVFA Lab, 2022

The LAVFA Lab installation at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, museum of modern and contemporary art, was created for families to celebrate the International Day of Families. The aim was to bring out the inner child by creating a slide into a pool of recycled plastic bottles and a wall table you could draw with bottle metal and plastic bottle tops. The playfulness of this installation proves that recycling waste is undeniably useful, something I aim to reciprocate in my work.

Fig. 9 Matt Calderwood. Untitled (Kettle’s Yard). 2009

Matt Calderwood knows how much pressure a lemon, wine glass or a steel shaft can take because he has experienced of these items in his work. In the playful utilisation of house-hold objects, his work frequently carries the potential for disaster.

He makes his constructions or performs something once without practising. This gives an immediacy to the work that I find fascinating. During the time spent investigating the actual properties of the household objects, the artist opens up both an emotional and intellectual reaction to these everyday objects.

Calderwood’s body of work seems closer to fiction than reality. However, the newly created environments determine how we think of, in an abstract way, the uncertain circumstances caused today by economical, ecological, and political crisis all over the world. The playfulness of their construction being the catalyst for their positive message. Making in this setting assumes the significant role of characterising the different connections among fictional and real that make up our contemporary lives.

Calderwood uses vivid colour objects adding to the general sense of playfulness. Colour is important in my work as Orban Pamuk said ‘I hear the question upon your lips: What is it to be a colour? Colour is the touch of the eye, music to the death, a word out of the darkness’.

Throughout time humanity always gave meaning to colour. Colour is seen when we register with our eyes the light and the information then is analysed by our brains. Because of this we all understand and perceive colour in different ways.

Process/Material

“Life is movement. Everything transforms itself; everything modifies itself ceaselessly, and try to stop it, tried to check life in mid-flight and recapture it in the form of a work of art, a sculpture or of painting, seems to me to be mockery of the intensity of life.” (Jean Tinquely)

Fig. 10 Phyllida Barlow, Bad Copies, 2012

But using everyday materials that are often discarded, Philippa Barlow’s practice is one of production and then deconstruction. Most of her work is built in situ and involves crushing, stretching, stacking, stocking and rolling as her methods of working.

My interest is in her frequent application of bright colours that give the installations a great sense of unlimited energy.

Another interesting aspect of her work is that her structure can appear on the point of collapse. This ads a tension to the work.

As Ina Cole said in her book From the Sculpture’s studio: Conversations with Twenty Seminal Artists, ‘the transience of your installations, and the way pieces are stacked in disintegrating formations, gives your work the quality of a collapsed city, ravaged by political savagery or natural disaster’. (Cole, 2021) Phyllida Barlow says that ‘the act of creativity is political by its very nature’ which I find compelling to use in my work.

Fig. 11 Phyllida Barlow, untitled, 2014

Barlow’s drawings seem to ‘break-down’ the space. I find interesting how they reveal the thoughts and processes behind the development of her sculptures. She said ‘with the other materials I’ll be going to discover - clay and plaster - there was a looseness, an approximation you could maybe do something that was incredibly bad, but there was a way of approaching it that could be very exciting, like just pushing it over, or allowing things to break’ (Robson, 2020)

Her concern with the physical properties and aesthetic possibilities of her materials is fascinating. It’s a visceral experience you get from the suspended materials in space. This idea of drawing in space, created in her work is alluring and inspiring.

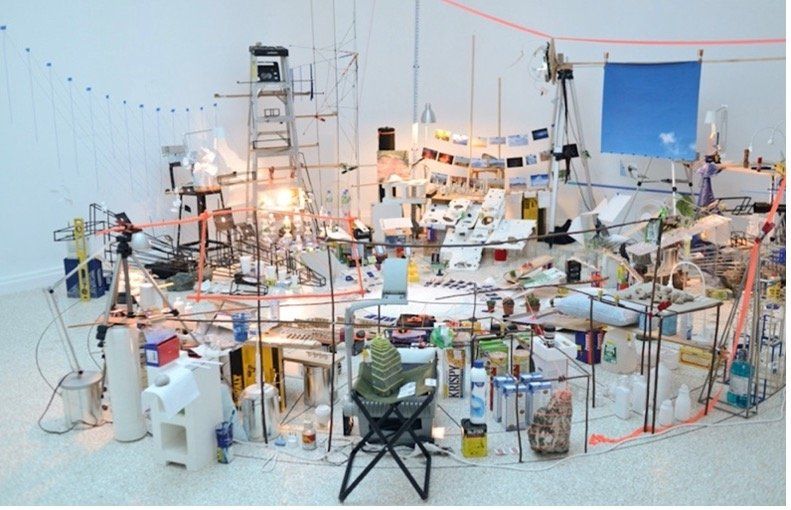

Fig. 12 Sarah Sze, Triple Point (Pendulum), 2013

The sense of fragility, transformation and constant change found in the work of Sarah Sze (1969-) is very relevant to my work. I am drawn to how her work questions the value that society places on objects. Also, how these objects at the same time place meaning on the moments and locations we inhabit

In her work Triple Point (Pendulum) (Fig. 12) from 2013 shown at the 55th Venice Bienalle, representing United States, Sarah created an installation that had as a central theme a sense of uncertainty and it seems that it is on a verge of collapse. I am intrigued by the tension she created in this work between wonder and anxiety with the help of the everyday objects used.

This tension comes from the sense that these objects somehow define the behaviour of the time they were made, like an echo chamber. Somehow the objects are more than just the sum parts of their materiality.

This is further enhanced by her using cheap everyday objects linking to consumer culture and following a tradition of early 20th century art movements, reflecting industrial culture.

When an individual object is removed from its use in the world to participate in a Sze environment, it leaves its previous function aside in order to participate in an entirely different universe. This reassignment of something familiar, whether a bottle cap or a smooth stone doesn’t change its intrinsic meaning; rather, it is Sze’s intention to absorb that intact meaning into a larger, more open-ended inquiry. Despite the factuality of each object Sze’s sculptures are organised towards search, as opposed to the discovery. This suggests that her oeuvre can be viewed through both a scientific and a philosophical lens, in addition to a purely aesthetic one. (Laura Hoptman for Enwezor, 2016, p.94)

In her collages using detritus and waste Sze creates connections in her work with present and future life. Whilst she uses the objects in a way that ‘puts the previous function of the objects aside’ the hauntological relationships that we have with these objects still remain and this helps create the attraction and impact of her work.

I believe that the semiotics of found objects when used in art are an integral part of the artwork itself, whether to trigger distant memories or create other a meaningful association particularly when associated with ecological narratives. Beyond this the objects themselves have an aesthetic appeal and the shapes and textures and mass can be used to further stimulate engagement with the artwork.

Bibliography

Albers, J. (2013) Interaction of color. Yale University Press.

Ammann, J-C. (2016) Alexander Calder & Fischli/Weiss. Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel.

Amstrong, E. (1996) Play/Things, Peter Fischli David Weiss: In a Restless World, Minneapolis, Walker Art Center, pp. 83-93

ART 21 (2019) Sarah Sze. [Online] Available from: https://art21.org/artist/sarah-sze/ (Accessed: 6.04.2022).

Batchelor, D. (2000) Chromophobia. Reaktion Books Ltd. London.

Bennett, J. (2010) Vibrant matter. Duke University Press.

Berger, John (1972) Ways of Seeing. London, Penguin Classic

Brooker, J. (2010) Found objects in art therapy. International Journal of Art Therapy, 15(1), pp.25-35.

Bogost, I. (2012) Alien phenomenology, or, what it's like to be a thing. University of Minnesota Press.

Boldrick, S.Dr. (2021) Michael Landy's Break Down: 20 Years [Online]. Available at: https://www.galleriesnow.net/shows/michael-landys-break-down-20-years/ (Accessed: 25.09.2021)

Cole, I. (2021) From the sculptor’s studio: Conversations with Twenty Seminal Artists. Laurence King Publishing.

Collings, M. (1987) The Stumbling Objects of Fischli and Weiss. Artscribe International. Nov/Dec p.33

Danto, A. C. (1996) Play/Things. Peter Fischli David Weiss: In a Restless World. Minneapolis, Walker Art Center. pp. 94-113.

Fox, J. (2021). The world according to colour: a cultural history. London: Allen Lane.

Groys, B. (1996) Play/Things, Peter Fischli David Weiss: In a Restless World. Minneapolis, Walker Art Center. pp. 115-121.

Enwezor, O., Buchloh, B.H. and Hoptman, L.J. (2016) Sarah Sze. Phaidon Press Limited.

Fischli, P. and Weiss, D. (2006) Peter Fischli, David Weiss: Equilibres. König.

Fjodorova A. (2013) Peter Fischli and David Weiss ‘Rock on Top of Another Rock’.

Frey, P. (2016) Alexander Calder & Fischli/Weiss. Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel.

Foster, H. (2015) Bad new days: Art, criticism, emergency. Verso Books.

Harman, G. (2018) Object-oriented ontology: A new theory of everything. Penguin UK.

Harrison, C. and Wood, P.eds. (2003) Art in theory, 1900-2000: an anthology of changing ideas. 2nd Ed. Oxford: Blackwell.

Horne, R. (2008) Everything must go!. London: Ridinghouse.

Johnson, E.H. (2019) Modern art and the object: a century of changing attitudes. Routledge.

Kathke, P. (2015) Opening Spaces for Opportunities. Art Education in Germany, p.29.

Landy, M. (2004) Semi-detached. London: Tate Publishing

Lynch, I. and Lynch, S. (2016). Peter Fischli and David Weiss, How to Work Better. New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

Malloy, V. (2016) Calder and the Dynamic Cosmos. Alexander Calder & Fischli/Weiss. Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel.

Manco, T (2014) Raw + Material = Art: Found, Scavenged and Upcycled. 2nd Edition London, Thames & Hudson Ltd.

Morton, T. (2021) All Art is Ecological. Penguin UK.

Morton, T. (2013) Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World. University of Minnesota Press.

Morton, T. (2010) The Ecological Thought. Harvard University Press.

Moszynska, A. (2013) Sculpture now. London: Thames & Hudson.

Obrist, H.U. (2018) 9th ed. A brief history of curating. Zurique: JRP/Ringier.

Peter Fischli and David Weiss (2021) [online] Available at: http://www.artnet.com/artists/peter-fischli-and-david-weiss/biography (Accessed: 21.04.2022).

Pray, M.O. (1988) Video: Causal Events and Relations at the ICA. Art Monthly (Archive: 1976-2005). (115), p.32.

Ruhrberg, K., Honnef, K., Fricke, C. and Schneckenburger, M. (2000) Art of the 20th Century. Taschen.

Robson, C. (2020) 50 Women Sculptors. Supernova Books/Aurora Metro Publications Ltd.

Simpson, P. (2021) The colour code: Why we see red, feel blue and go green. Profile Books.

Skulski, M., Huggins, A. (2020) General Ecology: The Story of the Understory of the Understory. [podcast] December 2020 [online] Available at: https://www.serpentinegalleries.org/art-and-ideas/general-ecology-the-story-of-the- understory-of-the-understory/ (Accessed: 20.04.2022)

Sooke, A. (2016) The man who destroyed all his belongings [online] Available from: http://www.bbc.co.uk/culture/story/20160713-michael- landy-the-man-who-destroyed-all- his-belongings (Accessed 25.07.2021)

Wijers, L. and Beuys, J. (1996) Writing as Sculpture: 1978-1987. Academy Editions Limited.

Vischer, T. Ed. (2016) Alexander Calder & Fischli/Weiss. Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel.

Zellen, J. (2010) Constructed realities. Afterimage, 38(3), p.27