Research and Critical Reflection

In my quest to delve into the profound concepts of Hauntology, constraint, and memory, I embarked on a journey of inspiration, drawing from the works of esteemed artists who fearlessly confronted the theme of constraint within the confining realm of the white cube. Among the artists who stirred my artistic senses and compelled me to unravel the intricate layers of these themes were Sarah Sze, Mike Nelson, Ai Weiwei, Mona Hatoum, Eva Gold, Louise Nevelson, Alexandre da Cunha, and Phillida Barlow.

Sarah Sze, with her captivating installations, entwines the ephemeral nature of memory with intricate arrangements of everyday objects. By meticulously constructing delicate and fragile environments within the white cube, she invites us to contemplate the transience of our experiences and the fragmented nature of our recollections.

Mike Nelson, on the other hand, masterfully creates immersive and disorienting environments that evoke a sense of uncanny constraint. His labyrinthine structures transport us into forgotten spaces, echoing with the ghostly whispers of the past. Through his skilful manipulation of architectural elements, Nelson confronts us with the eerie presence of forgotten histories and the haunting ghosts of bygone eras.

Ai Weiwei, a prominent figure in the world of contemporary art, fearlessly challenges political and social constraints through his thought-provoking installations. His works, often infused with elements of activism and dissent, serve as powerful reminders of the fragility of memory and the enduring impact of collective remembrance.

Mona Hatoum's compelling sculptures and installations evoke a sense of confinement and constraint, reflecting the artist's own experiences of displacement and estrangement. Her thought-provoking works prompt us to question the boundaries that confine us physically and mentally, urging us to confront our own limitations and the ways in which memory can be both a burden and a source of empowerment.

Eva Gold, with her explorations of Hauntology, deftly blurs the boundaries between past and present, creating a haunting sense of temporal dislocation. Her evocative works embody the essence of spectral memory, inviting us to navigate the ghostly landscapes where the echoes of the past reverberate through the present.

Louise Nevelson, a pioneering sculptor, transforms discarded materials into poetic assemblages that transcend the constraints of their humble origins. Her imposing sculptures, often monochromatic and monumental in scale, challenge us to reflect on the transformative power of memory and the significance of the forgotten fragments that compose our personal narratives.

Alexandre da Cunha's innovative approach to sculpture embraces found objects and materials, breathing new life into discarded and overlooked artefacts. By subverting their original functions and repurposing them within the white cube, da Cunha invites us to reconsider the constraints imposed by the mundane and to discover hidden narratives within the familiar.

Phillida Barlow, with her bold and expressive sculptures, confronts the limits of space and materiality, pushing against the confines of the white cube. Her monumental constructions disrupt the traditional gallery setting, forcing us to reassess the boundaries that define our surroundings and the possibilities that lie beyond them.

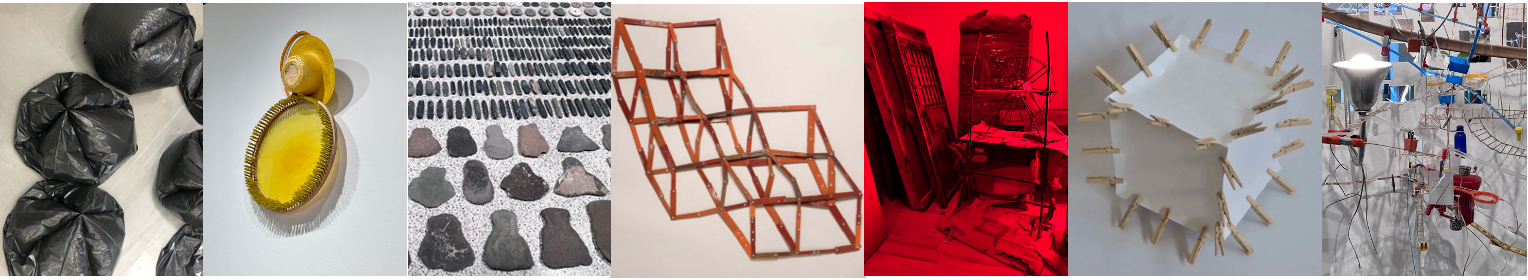

Inspired by the ingenuity and artistic prowess of these remarkable makers, I embark on my own artistic exploration, seeking to unravel the enigmatic interplay between Hauntology, constraint, and memory within the evocative realm of the white cube.

Coca-Cola Bottle and Cans and Hauntology

In my artistic practice, I have chosen to incorporate a unique medium – my own discarded Coca-Cola bottles and cans. By repeatedly utilizing soda cans in my creations, I aim to shed light on various aspects of our society, including consumer culture, waste management, social dynamics, political landscapes, and environmental concerns. This deliberate choice of material serves as a powerful symbol, inviting viewers to contemplate the broader implications and consequences of our consumer-driven world.

Coca-Cola, as a globally recognised brand, holds significant cultural presence and can be explored in the context of Hauntology in art. The concept coined for the first time by Jacques Derrida, refers to the lingering ghosts of the past that haunt the present, evoking a sense of nostalgia, longing, or uncanny familiarity. Artists engaging with Hauntology often delve into the examination of cultural artefacts and symbols that have become ghostly remnants of a bygone era.

By incorporating Coca-Cola imagery into my artwork, I tap into the collective memory, creating pieces that provoke reflection on the power dynamics of capitalism, the transient nature of consumer culture, and the intriguing allure of nostalgia. These artworks navigate the boundary between the familiar and the uncanny, inviting viewers to contemplate the haunting presence of cultural artieacts like Coca-Cola within our collective consciousness.

Furthermore, my work goes beyond the commentary on consumerism. It delves into broader social and political issues by manipulating and arranging the Coca-Cola cans and bottles. Through this process, I explore the complexities of power dynamics, class struggles, and societal inequalities. By juxtaposing familiar branding with unconventional artistic techniques, I challenge viewers to question the status quo and consider alternative perspectives.

Additionally, my artistic endeavours touch upon pressing environmental concerns. Repurposing discarded Coca-Cola cans and bottles becomes a statement against wastefulness and highlights the detrimental impact of single-use products. By showcasing the hidden beauty and value within these seemingly insignificant objects, I invite viewers to contemplate sustainable practices and the importance of responsible consumption.

Furthermore, the field of eco-art has gained prominence in recent years, focusing on ecological awareness and sustainability. Artists engaging in eco-art utilize various materials, techniques, and installations to confront environmental challenges and advocate for change. By aligning my practice with these larger artistic movements, I aim to contribute to the ongoing dialogue surrounding art's potential to foster critical thinking, raise awareness, and inspire positive transformation in society.

In summary, my artwork, utilizing my own discarded Coca-Cola bottles and cans, serves as a visual and conceptual commentary on consumer culture, waste, social dynamics, political landscapes, and environmental concerns. By repurposing these objects, I hope to stimulate contemplation, provoke thought, and encourage viewers to reflect upon their own roles within the intricate tapestry of our interconnected world. Simultaneously, the incorporation of Coca-Cola imagery invites viewers to explore the haunting presence of this iconic brand within our collective memory and contemplate its cultural significance.

Fig. 1 Paul Neagu, Box, Tactile Object (Receptacle), 1972; Fig. 2 Carmen Van Huisstede,

Box of Stories, 2023

Paul Neagu's Palpable Objects

Neagu, a Romanian-British artist, broke free from the conservative confines of the local artistic system during his time in Romania. He achieved this by immersing himself in movements such as Op Art, Kinetic Art, Neo-constructivism, and cybernetics. In his influential

Palpable Art Manifesto of 1969, Neagu advocated for art to transcend its purely visual nature. He demanded that art engage all sensory perceptions, incorporating touch, smell, taste, and hearing. From 1969 onwards, Neagu crafted tactile objects that exhibited a diverse materiality. Each box he created contained a medley of objects and materials on its inner surface, ranging from bread, feathers, and metal blades to mosaic or glass pieces, velvet, matchsticks, and even human skin.

The recurring cellular partitions in Neagu's objects and drawings played a pivotal role in highlighting the relationship between the parts and the whole, the unit and the system, the cell and the organism. Neagu's exploration of sculpture's vocabulary led him to conceive his most emblematic invention, the hyphen, in the mid-1970s. This entity, seemingly simple yet conceptually intricate, delved into the formal and symbolic meanings of basic geometric shapes. Moreover, the hyphen incorporated elements from both cultural and vernacular sources. Neagu developed this vocabulary through a study of peasant crafts and traditions, spanning regions from Romania to China and from Greece to Scotland.

Having moved to London in 1970, Neagu continued to create his "tactile" and "palpable" objects until 1972. Originally designed as suspended objects, these tactile objects aimed to distance themselves from being confined to a pedestal. Neagu explained in 1986 that the more a sculpture moves away from its plinth, the less it becomes a singular object of significance. His "palpable objects" were constructed artworks with articulated elements, intended to be physically manipulated by the viewer. Many of these pieces incorporated boxes or compartments filled with various tactile substances like fabrics or leather.

Neagu's debut exhibition in Great Britain took place at the Demarco Gallery in Edinburgh as part of the 1969 Edinburgh Festival. The exhibition featured numerous constructed objects, assembled from different found elements, and suspended from the ceiling. The dark, unlit rooms intensified the sensory experience for visitors, who navigated the space by touch alone, individually exploring and sensing the objects. Neagu aimed to create works that transcended purely visual considerations and instead focused on form, texture, and the evocative associations these qualities elicited.

In his 1969 "Palpable Art Manifesto!", Neagu asserted that the eye had become fatigued, perverted, and shallow due to its degenerate cultural state, influenced by photography, film, and television. He argued that for art to survive as plastic art, it needed to abandon its purely visual aesthetic and embrace an organic and unified aesthetic that engages the fresh and pure senses. Neagu contended that one could apprehend things more fully and profoundly with ten fingers, pores, and mucous membranes than with just two eyes. He concluded that palpable art was a new delight for the "blind" and a thoroughly three-dimensional study for the "clear-sighted."

During the early 1970s, Neagu also created figurative tactile objects that shared construction techniques and intentions with his tactile objects. The Great Tactile Table, first exhibited at the Sigi Krauss Gallery in London in 1971, exemplifies this approach. It consisted of numerous individual boxes forming figurative shapes, inviting spectators to dip their fingers and feel various substances and textures. These works not only engaged viewers physically but also conveyed metaphorical significance through their compartmentalized formal structures. The sculpture's cellular nature symbolized the composition of the human body, composed of individual parts and sensations, as well as drawing parallels to broader human structures like society, composed of discrete components. The underlying message was that both the individual and society as a whole constantly strive for unity and equilibrium.

In 1972, Neagu further expanded his ideas with the creation of White Tactile Object with Hinges. This piece featured a wooden box, painted white, with a hinged lid along one edge. The interior of the box was divided by several cardboard matchboxes, and the spaces between them were filled with brown-painted newspaper papier-mâché. Representing an extension of his "palpable" and "tactile" objects, this artwork operated visually but aimed to evoke tactile sensations through the viewer's visual experience. The deliberately encrusted, amorphous, and organic appearance of the object strongly suggested its tactile nature.

My interest in his work comes from experiencing a similar upbringing to him, growing up in a communist regime. This influenced the way we communicate ideas.

Mona Hatoum, all of a quiver, 2023

Mona Hatoum is a contemporary artist renowned for her thought-provoking and challenging artworks that delve into themes like displacement, identity, power, and vulnerability. She employs various mediums such as sculpture, installation, video, and performance to transform familiar objects and spaces into unsettling and unfamiliar experiences.

One of her notable installations,

all of a quiver, is located in the Kesselhaus at the Berlin KINDL - Centre for Contemporary Art. It consists of a large metal grid structure suspended by a pulley system from the ceiling. The installation serves as the concluding part of Hatoum's retrospective in Berlin and encapsulates recurring themes in her artistic practice, including displacement, destruction, conflict, metal grids, and cages. These themes are deeply connected to her Palestinian background, as her parents were refugees displaced during the Nakba in 1948, and Hatoum herself experienced displacement due to the civil war in Lebanon.

Hatoum's work reflects the concepts of displacement and collapse throughout her life and career. She explores these ideas in pieces like

Remains of the Day

and

Mobile Home, which evoke the remnants of domestic life and the symbolism of migration and border violence, respectively. Despite these allusions to destruction,

all of a quiver maintains an ambivalent quality, hinting at the possibility of hope and resilience.

The installation also alludes to the human body, with the structure's creaking and groaning resembling aging bones and the act of re-erection symbolising the birth of the next generation. The title,

all of a quiver, highlights the trembling during the re-erection as the fundamental condition and unifying force behind the piece. Hatoum suggests that both glory and defeat are transient.

Another intriguing artwork by Hatoum is

Home, exhibited in Berlin in 1999. It consists of electrified domestic objects interconnected by a web of electric wires, transforming the familiar setting of a home into a space charged with danger and tension. This installation explores the experience of displacement and the loss of a secure sense of belonging.

In her broader body of work, Hatoum tackles issues such as gender, politics, and the human body. She juxtaposes contrasting materials to challenge viewers' preconceptions and stimulate introspection. Through her art, Hatoum encourages us to question power dynamics, social norms, and the boundaries that shape our lives.

Eva Gold,

City of Rooms (Part Two), 2023

Gold's artistic practice revolves around narrative-driven methodologies that incorporate various elements such as objects, writing, materials, and spatial arrangements to communicate stories. Within this framework, individuals find themselves in a peculiar position where they observe others being observed, transcending passive viewership to become uncomfortable voyeurs. As a result, spaces undergo a detachment from their original contexts.

In our society, which increasingly takes on the roles of both producers and consumers of visual media, the incessant act of (re)producing oneself emerges. Furthermore, we willingly contribute to the perpetuation of surveillance technologies. This essentially transforms us into architects and prisoners of a self-created panopticon, perpetuating a state of constant observation and control.

The concept of the cinematic gaze has long been discussed as a form of surveillance technology. Cinema portrays its audience as voyeurs, while the protagonists serve as onlookers who portray the "other" based on factors such as sexuality, race, gender, or class to advance the narrative. This has a formative impact on the viewer, shaping their understanding and regulating social perception. In the current age of social media and the pervasive influence of visual culture in our social and political spheres, this phenomenon intensifies. As we all become producers and consumers of our visual media, we not only endlessly (re)produce ourselves, but we willingly contribute to the technology that surveils us. We simultaneously create and are confined within a panopticon of our own making.

Her work prompts me to contemplate and incorporate the concept of surveillance into my own works. I find myself captivated by the notion of observing individuals who are themselves under observation.

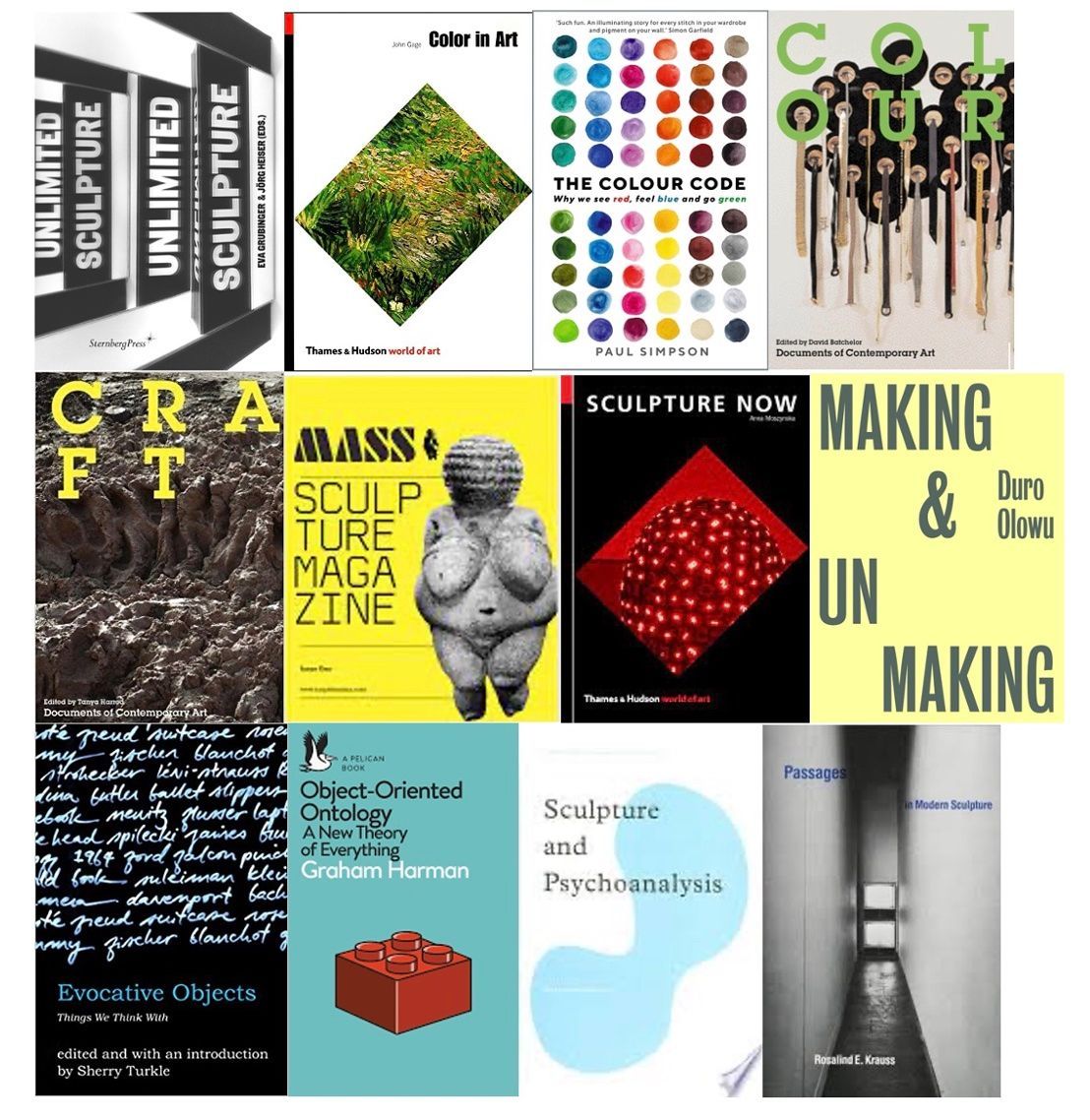

Allen, J., Ammer, M., Grunbinger, E., Heider, A.V.D., Heiser, J., Hirsch, N., Hochleitner, M., Mir, A., Rehberg, V.S., Van der Straeten, A. and Verwoert, J., 2011.

Sculpture Unlimited. Sternberg Press.

Batchelor, D., 2008.

Colour. Documents of Contemporary Art. Co-published by Whitechapel.

Curtis, Penelope & Wilson, Keith (Eds). 2011.

Modern British Sculpture. Royal Academy of Arts, London.

Enwezor, O., Buchloh, B.H. and Hoptman, L.J. (2016)

Sarah Sze. Phaidon Press Limited.

Gage, J, 2006.

Colour in art. Thames & Hudson.

Grubinger, E., Heiser, J., Domanović, A., Fischer, M., Heinich, N., Leckey, M., Parikka, J., Sauer, C. and Vermeulen, T., 2015. Sculpture Unlimited 2: Materiality in Times of Immateriality. Sternberg Press.

Harrod, T., 2018.

Craft. Documents of Contemporary Art. London: Whitechapel Gallery.

Harman, G., 2015.

Object-oriented ontology. The Palgrave handbook of posthumanism in film and television, pp.401-409.

Hirst, N., Calderwood. M. 2022.

A conversation between Nicky Hirst and Matt Calderwood, Sculpture Magazine, (Issue One), pp.47-48.

Krauss, Rosalind. 1977.

Passages in Modern Sculpture. London: Thames and Hudson,

Lange-Berndt, P., 2015.

Materiality. Documents of Contemporary Art. London: Whitechapel Gallery.

Manco, T. 2014.

Raw + Material = Art: Found, Scavenged and Upcycled. 2nd Edition London, Thames & Hudson Ltd.

Morton, T. 2021.

All Art is Ecological. Penguin UK.

Morton, T. 2010.

The Ecological Thought. Harvard University Press.

Moszynska, A. 2013.

Sculpture now. London: Thames & Hudson.

Nelson, S., Hussain. K. 2022.

Bronze: Stephen Nelson and Kabir Hussain in conversation, Sculpture Magazine, (Issue One), pp.61-65.

Olowu, D. ed., 2016.

Making Et Unmaking. London: Ridinghouse.